Platform-as-a-Channel: A New Model Disrupting the Channel Partner Ecosystem

Defining the Traditional Channel Partner

In 1997, MarketBridge’s CEO Tim Furey published The Channel Advantage. It became a best-selling business book, and a go-to resource for executives looking to navigate a new world in which technology was lowering the cost-per-touch every year. Smart companies realized that they needed to move away from expensive, one-on-one direct field sales if they wanted to compete on lower-value transactions. Telesales and e-commerce quickly became standard for sub-$1000 transactions, and the partner channel exploded in the technology industry. Of course, for many years, partner channels had dominated other industries—insurance had its agents, the consumer had its supermarkets, and manufacturing had its distributors.

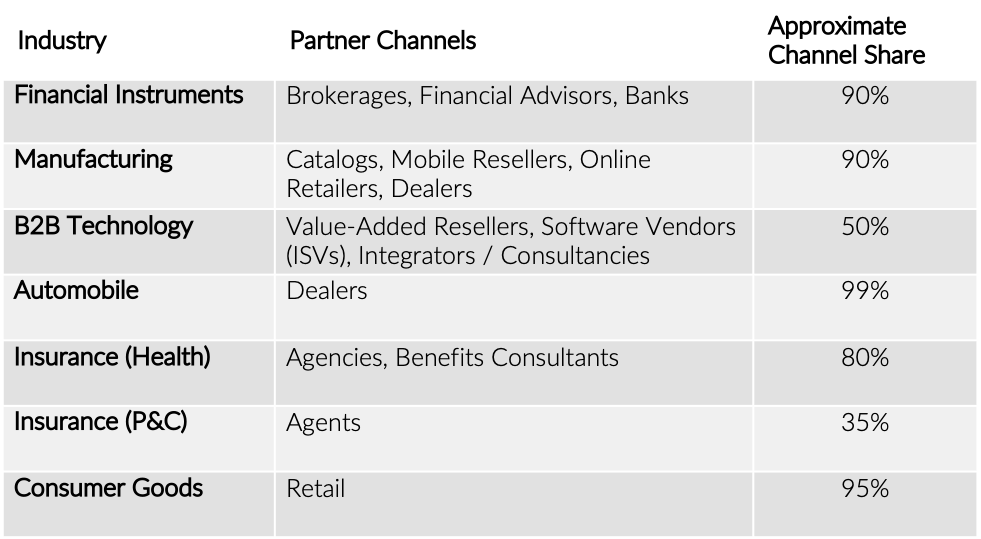

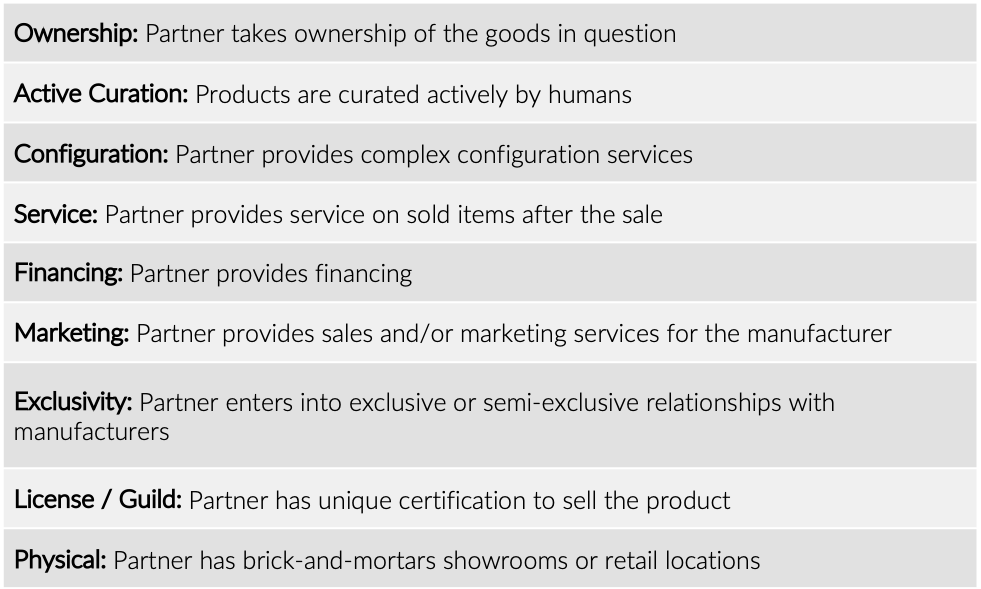

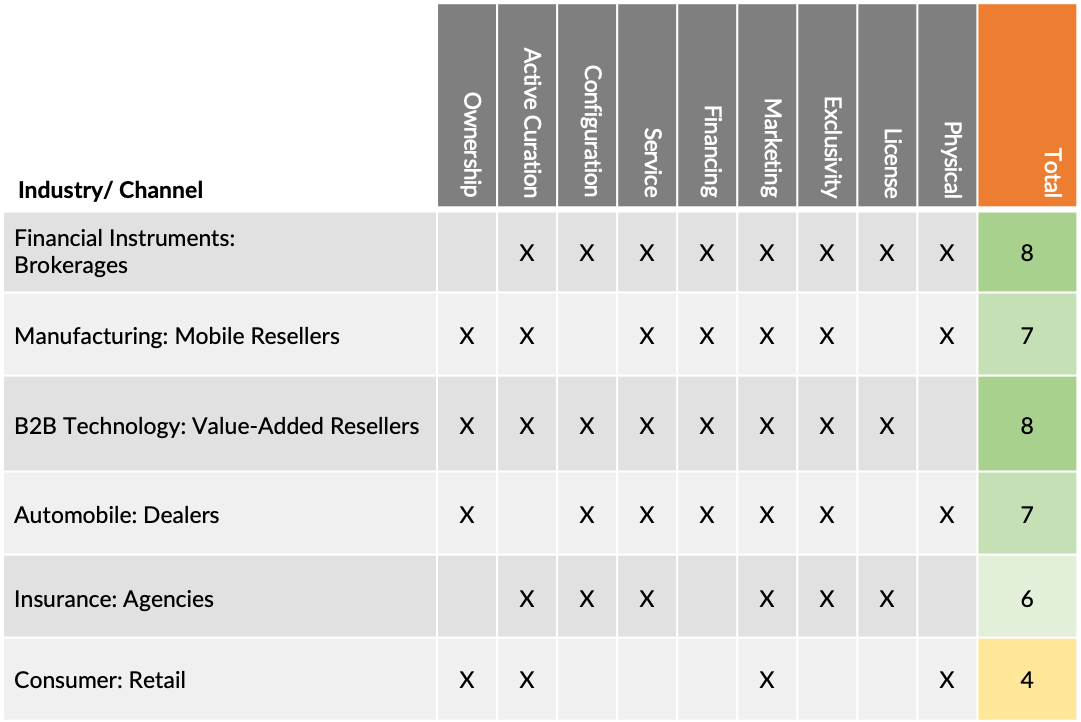

For each of these industries, the partner channel model hadn’t changed much until a few years ago. Most groceries and consumer goods traveled through supermarkets; most cars were sold through dealers, and most manufacturing items were sold through distributors. These traditional channel models have some combination of nine traits in common, depending on the industry. Typically, for a partner to meet the definition of a “traditional” channel partner, they have to meet at least three of these criteria, but most meet many more:

Concretely, here are how some of the “traditional” industry partner models are scored against this construct:

In return for these services, channel partners buy at a lower price from manufacturers (the wholesales price), and then sell at a higher price to consumers. This “channel margin”—which can vary widely by industry between a few basis points for financial products to upwards of 50% for luxury goods retailers—can be thought of as the service charge for marketing. In some cases, additional fees (co-op fees, for example) are paid to retailers / channel partners explicitly for marketing support.

The Rise of the Platform

As buzzwords go, “platform” is riding high. Everyone has a platform. If you call a piece of software a “platform” instead of an application, it seems like you get a valuation bump. Everyone wants in on the game, but what is a platform, really?

When Amazon was sued by family who had purchased a hoverboard through the site which subsequently exploded and burned down their home, the crux of Amazon’s defense was that they were a platform, not a retailer. The hoverboard was sold by a third-party seller; Amazon just facilitated the transaction. This struck many as a sleezy legal tactic to avoid paying out the lawsuit. Indeed, a recent appeals court judgment sided with the family, that Amazon did bear some responsibility for knowing what was being sold through their platform.

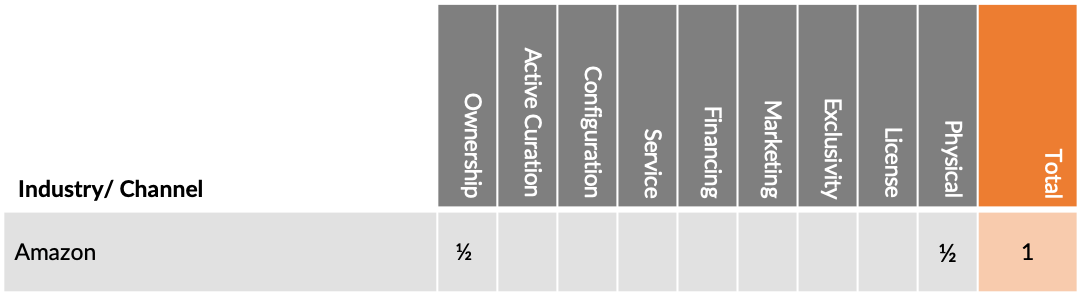

Amazon is certainly thought of as a retailer, but let’s score them against the above rubric:

I gave them half a point for ownership because while Amazon does have warehouses, in the case of the hoverboard, Amazon was not stocking the incendiary-device-disguised-as-a-mode-of-transport in it’s now somewhat infamous warehouses; the hoverboard was drop-shipped from the factory in China. I give them a grudging ½ on physical because, yes, Amazon now has a few brick-and-mortar stores, and bought Whole Foods. But, on all the other columns, they are a clear no.

- Amazon does not actively curate products. Products are bumped up on listing pages via an algorithm.

- Amazon certainly doesn’t figure, assemble, or help consumers at all with their purchases.

- Amazon is patently uninterested in servicing.

- Amazon does not offer financing, unless you count the Amazon credit card, which I view as more of an affinity product than a true financing vehicle.

- Amazon certainly isn’t interested in exclusivity agreements.

- Amazon has no special licenses to do anything.

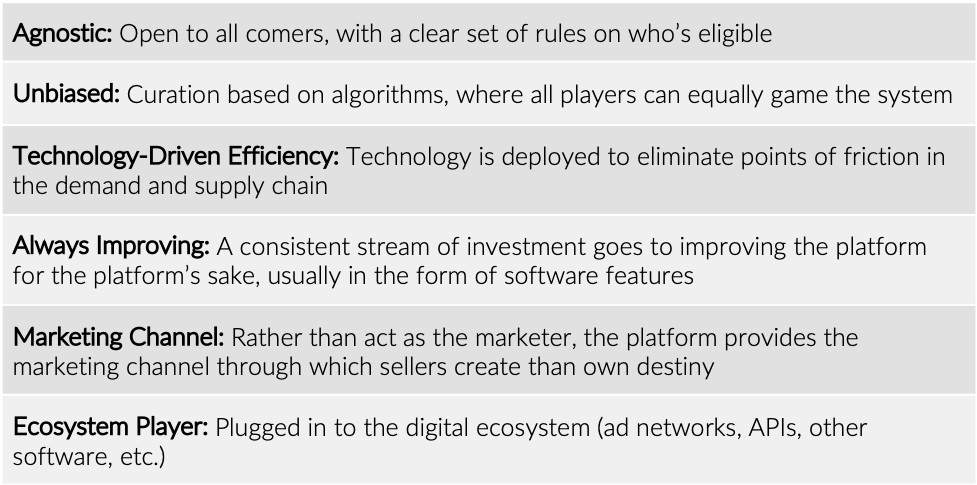

We’ve shown pretty convincingly that Amazon isn’t a traditional channel partner, but what are the unique “positive” traits that make a platform a platform, and make Amazon so successful? I’d argue that there are six unique traits that make a platform a platform:

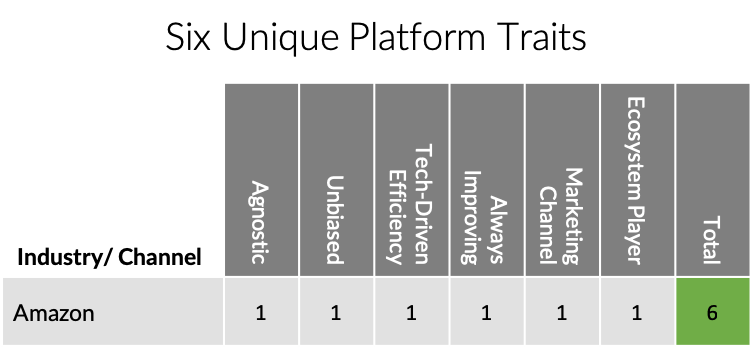

Looking at Amazon this way, it’s obviously 6/6:

Let’s look at some of the specific ways that Amazon aggressively works to hit these six criteria:

- Agnostic. Anyone can list on Amazon. Some complain that Amazon offers too much variety because it is such a literal jungle of stuff.

- Unbiased: While some might quibble that Amazon’s product pages are not unbiased at all—in fact, they are gameable—the rules of the games are known, and loopholes are shut down. Increasingly, to get to the top of the product page, the manufacturer (or partner—because distributors use Amazon, too) just has to work harder.

- Tech-Driven Efficiency: It’s easy for buyers and sellers to use Amazon, because everything has been made easy, lowering friction. From one-click ordering to Prime to an everything-is-an-API approach to fulfillment, the relentless drive to efficiency ultimately makes consumers and manufacturers “go for the default.”

- Always Improving: Whereas retailers, VARs, or agencies spend mostly on ongoing operations—mainly in the form of people, office space, and so on, Amazon spends mostly on software engineers and product managers who create and improve valuable assets, usually in roughly two-week sprints.

- Marketing Channel: Amazon doesn’t market for manufacturers, but it provides all of the plumbing and hardware for them to do the marketing.

- Ecosystem Player: Amazon will happily link into the broader ERP and AdTech landscapes in the spirit of reducing friction, knowing that they’ll win down the road as manufacturers figure out that “it’s just easier.”

Winning in the Platform-as-a-Channel World

Amazon is clearly the leading platform-as-a-channel in the world, but this blog post isn’t for Amazon executives; it’s for channel partners looking to “platformize” their business; for software companies trying to become a channel; or for manufacturers looking to find the platforms that will drive go-to-market success over the next decade.

As an aside, it seems clear that Amazon’s strategy is to become the platform for literally all economic activity worldwide, or at least in the United States and Europe. Given the economics of platform businesses—massive valuations + a software-based business model + network effects driving concentration—this certainly seems feasible. If that happens, perhaps the best strategy is just to acknowledge the mothership, and work with it. However, some government action will happen before 80% of GDP flows through Amazon, right?

Platformizing a Traditional Distribution Business

A traditional distributor starts with many advantages over a software platform looking to enter their market. They have strong industry expertise; may have guild / license barriers in place (for example, in the case of State licensing for insurance); a strong base of customers; and strong relationships with manufacturers / product providers.

But, it’s many of the competitive motes that have been erected over the course of becoming a world-class channel partner that will prevent success as a platform business. Exclusive arrangements or conflict-of-interest laden investment arrangements are hard to get around for companies trying to truly become a platform. Many distributors are unwilling to kill the goose that is laying the golden eggs.

Another challenge for traditional distributors is technology. A traditional retailer might think that just building (or buying) a robust e-commerce platform is enough, but what is truly required is transitioning a significant—think 25% or more—portion of annual operating budget to agile development. This will give retailers and accountants heartburn, because “agile development” by definition isn’t over after something is built. This isn’t like building a store, where after 18 months an asset is on the books, and another store can be built. Instead, technology becomes a part of ongoing labor. Only by continuously churning out improvements can a platform survive and thrive. After all, everyone else is doing the same thing.

Many traditional channel partners have evaluated the business and technology costs of platformizing their businesses and have instead chosen to become “Amazon agencies.” An Amazon agency is a vendor who essentially acts as the last mile for manufacturers to get their products up on Amazon. They handle listings, photos, pricing, and tweaking all of the little things that drive #1 placement on the biggest platform of them all. In exchange, they either take a commission or a flat fee (there are multiple models out there.) The jury’s still out on this approach, but it seems to me to be a stopgap, until manufacturers get smarter and Amazon’s tools get easier to use.

Software Applications Becoming a Platform

Salesforce.com was the poster child for a software company monetizing itself as a channel. In the early 2000s, Salesforce launched its AppExchange, where different applications could be purchased by Salesforce users to do things like score leads, enter timesheets, or pretty much anything else imaginable. Salesforce never wanted to be just a CRM system. They realized that with their dynamic relational database platform and user-accessible code execution system, they could literally become the substrate for all enterprise applications.

Even though Salesforce has been wildly successful, they have not been as successful as a distribution platform. The issue is Salesforce’s very high PEPM (per employee, per month) licensing fees, which make distribution at scale very difficult for smaller software companies. Companies are also unwilling to add other software applications on to an already expensive Salesforce backbone (which is taking something like $80-$100 PEPM for its base functionality.)

The next set of potential “platform as a channel” software kings are the freemium companies. Slack is a great example. Slack’s genius is that it self-expands into organizations using employees as advocates, and its free version is quite robust. Slack is also not greedy; its fees are on the order of a few dollars per month PEPM. Slack is also more of a “pipe” than a “water” company. Slack doesn’t have any real IP, like Salesforce’s core CRM data structure. It depends on others to provide the water, so for now, there’s little conflict of interest. Slack, like all good platforms, focuses on making the last mile to the customer as friction-free and fun as possible.

Microsoft has taken a different approach. Microsoft started with function; every white-collar worker in the world seemingly uses the Office Suite. Microsoft then built Teams to essentially imitate Slack, and then bundled it all together in the super-easy Office 365 platform. Office 365 is perhaps the ideal platform-as-a-channel: It has massive penetration; it is unlikely that anyone will stop using Excel or PowerPoint in the next ten years; and billing is already baked in (corporate credit card, anyone?)

Finally, there are the infrastructure-based platforms-as-channels. Amazon Web Services (AWS) is essentially on-demand storage and processing power; what you do with it is up to you. Initially, most of the code running on AWS was custom software, but increasingly, “cloud appliances” are being sold through AWS to work with the custom software out there. These “cloud appliances” can be almost anything—AI, data streams, business productivity—but they are designed to work with open endpoints, in almost endless configuration options. Again, AWS’s job as a platform is to make the last mile or delivery as friction-free as possible—and not to be too greedy when it comes to its own fees.

Taking Advantage of Platforms as a Manufacturer

Many manufacturers make the critical mistake of investing in platforms in an attempt to get into the platform-as-a-channel game. These investments might make a lot of sense on paper, but the minute they close, they lose their value, because of perceived conflict-of-interest. No matter the assurances, buyers know that ultimately, the manufacturer with a significant stake in the platform will get special treatment. At the same time, other manufacturers will stay away, erasing one huge benefit of a platform—a huge amount of unbiased selection.

Instead, manufacturers should invest in the technology to integrate with platforms as easily as possible. In the manufacturing industry, this means investing in product management platforms and APIs. In the insurance industry, it means investing in plan configuration and enrollment APIs, and updating billing systems. This focus on back-end vs. front-end technology will be unappealing on its face to salespeople focused on quarterly results, but over the long run, revenue will increase as more and more platforms are integrated without manual efforts (fewer or no pen and paper or email transactions, and mostly APIs.)

At the same time, manufacturer marketing teams should spend their time learning the advertising technologies and policies of the platforms they will increasingly rely on to move product. It’s shocking how successful companies can be on Amazon just by spending a few days reading the rules of the road and playing around with the built-in marketing tools on the platform. Again, resist the temptation of building something new from scratch; instead, use what’s out there, and focus on what you do well.

Conclusion

Platforms-as-a-channel aren’t really new, but they are reaching an inflection point in sophistication, awareness, and distribution market share. Traditional channel partners, software companies, and manufacturers all have a different to-dos, and they aren’t necessarily intuitive. Think carefully about your platform-as-a-channel ecosystem, and where to place your bets.